Mindfulness in Early Years

Mindfulness is such an important topic in today’s busy world. Early Years Practitioners can provide children the best opportunities to learn and use their natural skills in mindfulness to develop happiness, calm, focus and emotional wellbeing. Jon Kabat-Zinn coined the term mindfulness with a definition that is well regarded today in the field of education. He defines mindfulness as “paying attention in a particular way on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally.”

The ability to self-regulate and manage a range of emotions gives children self-confidence in their daily life to manage different social contexts that they may encounter, preparing them from a young age to express their thoughts and feelings.

Here are some easy to implement, fun and effective mindfulness activities, techniques and tips that you can introduce to children during the day as part of the daily routine in your setting. These activities are designed to be implemented as and when required spontaneously when you think that a child or group of children will benefit from such an intervention.

Activity One: Just One Breath

Find a relaxing place indoors or outdoors for children to sit and set a timer for 1-2 minutes. It will take time for children to settle so allow at least 5 minutes in total for this activity.

Ask children to sit and start to notice how they feel. How do their legs, arms, tummy, and head feel? Ask them to notice any sounds they can hear around them. When the children are settled and connected with their breath, ask them to take a big breath in and then blow out, (“like a dragon blowing out fire, making a whoosh sound.”)

Ask them to take another breath imagining their belly puffing up like a big balloon then let it all go! Let this continue for a few more breaths, repeating the words inhale, exhale or breathe in and out.

Benefits: This brings feelings of calm and quiet if it has been a busy morning or afternoon. Improves brain function and wellbeing for children and concentration.

Activity 2: Sunshine Heart Pose

Practice this simple moving activity with a child or small group of children. Slowly raise your arms forwards, out to the side and then up to the sky. Look up and reach for some sunshine, hold this in your hand and bring it down to your heart centre. Pause, take a soft breath the air in through your nose and out through your mouth and relax.

Benefits: Children feel the air being pushed forwards, to the sides and upwards as they move their arms and hands. This silences the mind and helps it to focus.

Activity 3: Create a Calm Cave or a Calm Corner

Gather a group of children together and plan an area of the nursery, home or classroom to create a calm cave as a quiet place for relaxation. Use a range of materials to create the cave so that children are integral to the process. Include a range of cushions, soft colours and natural materials to enable a calming environment, with music CDs for children to rest and feel calm in.

Benefits: Quiet spaces for children will provide them with opportunities during the day to go and rest.

Activity 4: Morning Mantra for All

Starting the day at nursery or reception class for children can be a tearful, upsetting or key transition that they encounter in their day. Therefore starting the day using positive words and instilling positive thoughts is beneficial to their wellbeing.

Therefore start by asking children to sit in a circle, with nice straight backs. Encourage children to close their eyes and start to notice how they feel, taking a few deep breaths – breathing in and breathing out. Do they feel calm?

Then say the following words together:

I am feeling calm; I am happy; I am healthy; I always do my best; I am kind and caring;

Benefits: It is important for adults to praise children using positive language and also encourage children to learn positive words and let them think good thoughts.

Written by Yasmin Mukadam

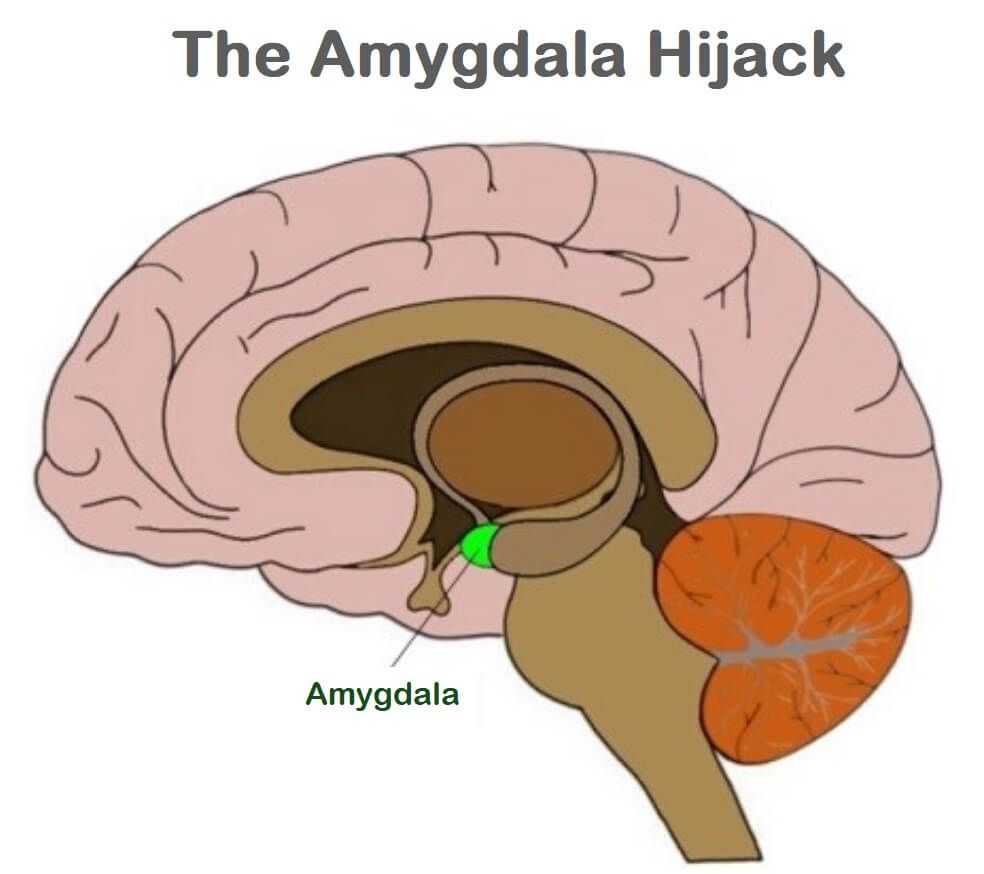

Did you enjoy reading this blog? If you want to learn more about neuroscience, focusing on the early years from birth to 7 years old, then take a look at our NCFE Cache Level 2 award – Introduction to Neuroscience in Early Years.