As both a nutritionist and a parent, I can tell you that ensuring toddlers get a balanced diet during their formative years is crucial. Between ages 1 and 3, these little ones experience tremendous growth—physically, mentally, and emotionally. Those who care for toddlers play a vital role in shaping their eating habits, which will impact their health for years to come.

Let’s dive into what you need to know to support the toddlers in your care, along with some practical tips, expert insights, and a sprinkle of delicious recipes to make meal planning a breeze.

Why Nutrition Matters So Much in Early Years

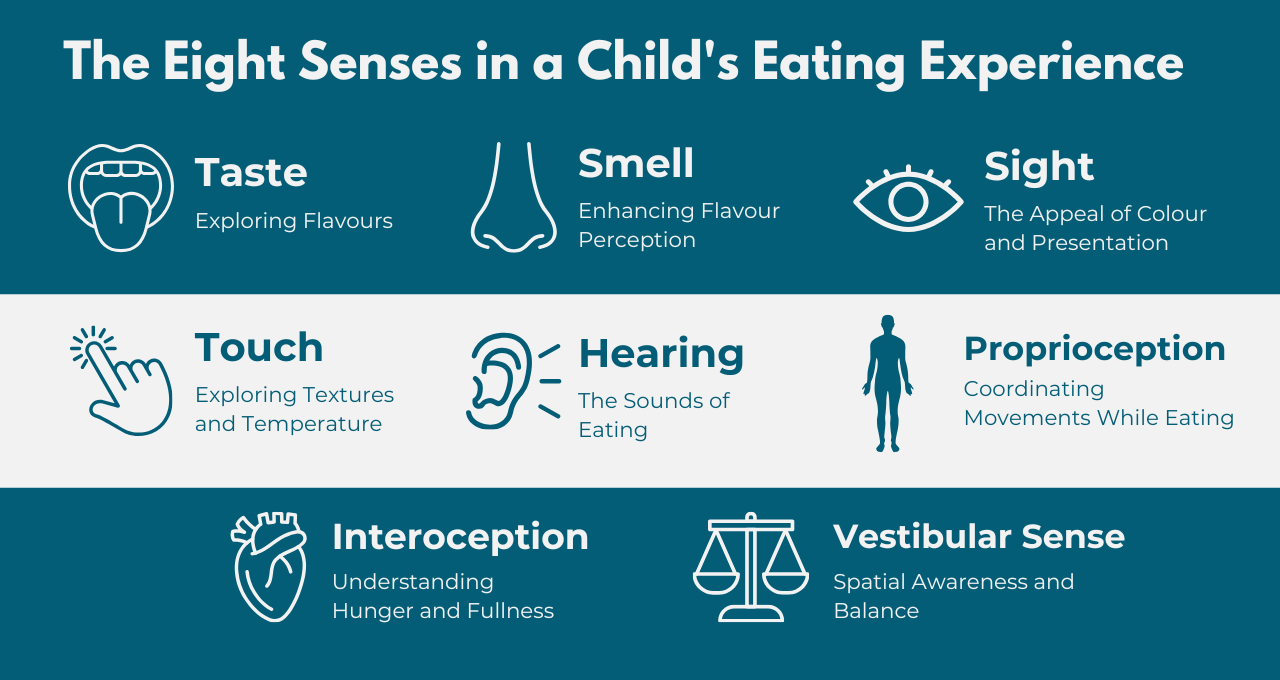

From their first steps to their first words, toddlers are in a whirlwind of development. Proper nutrition fuels their growing muscles, sharpens their minds, and bolsters their immune systems. Yet, it’s also during this time that many toddlers can become picky eaters, developing strong preferences (and aversions) to certain foods. Understanding the “why” behind nutrition can help you make informed choices when planning meals.

For instance, did you know that iron is vital for brain development? A deficiency can hinder cognitive function and affect learning abilities later on. Similarly, healthy fats are essential for brain development—something to keep in mind as you plan those meals!

Essential Nutrients for Toddlers

Toddlers have tiny tummies but big energy needs, so every bite should be packed with nutrition. Here’s what to focus on:

- Protein: Supports muscle and tissue development. Aim for around 15-20 grams per day. Think chicken, lentils, eggs, and tofu.

- Fats: Don’t shy away from healthy fats—they’re crucial for brain development. Great sources include avocados, seeds, full-fat dairy, and oily fish.

- Carbohydrates: These are your energy providers. Opt for complex carbs like whole grains and sweet potatoes to keep little bodies fueled throughout the day.

- Vitamins and Minerals:

- Iron: Think red meat, beans, and fortified cereals for those little brains.

- Calcium & Vitamin D: Dairy, fortified plant milk, and even a bit of sunshine are essential for strong bones.

- Vitamin C: Citrus fruits and bell peppers not only help with iron absorption but also keep those immune systems strong.

Cultural Sensitivity in Meal Planning

Living in a multicultural society means that caregivers often care for children from various backgrounds. It’s crucial to be aware of different dietary restrictions, whether they stem from religious practices or family traditions.

For example, when planning meals, consider the following adaptations:

- Halal: Use halal-certified chicken or beef.

- Kosher: Avoid shellfish and ensure meat and dairy are not served together.

- Vegetarian/Vegan: Swap out animal proteins for lentils, beans, and tofu.

Understanding Portion Sizes and Monitoring Growth

Ah, the age-old mystery of toddler appetites. One day they’re devouring everything in sight, and the next, they might barely touch their food. It’s essential to adapt to these cues. But how can you keep track of whether they’re getting enough nutrition?

Using growth charts from the NHS can help you monitor toddlers’ weight and height to ensure they’re on the right track. If you notice any concerning trends—like significant weight loss or excessive eating—don’t hesitate to reach out to parents for a chat. Open lines of communication are key.

Creating Positive Mealtime Experiences

Mealtime is not just about filling tummies; it’s also about fostering a love for food. Here’s how to make those moments count:

- Variety: Keep things interesting by introducing new foods alongside familiar favourites.

- Involvement: Let toddlers help with simple tasks, like washing veggies or stirring. When they’re part of the process, they’re often more excited to eat.

- Avoid Pressure: Pressuring a child to eat can create anxiety. Instead, encourage them to explore their food at their own pace.

Managing Picky Eating

Every child goes through a picky eating phase, and that’s perfectly normal! Here are a few strategies to help navigate this tricky terrain:

- Pair Familiar with Unfamiliar: Try serving a new vegetable alongside their favourite dish.

- Stay Calm: Don’t react negatively if they refuse something; just offer it again later.

- Model Healthy Eating: Let them see you enjoying a variety of foods!

If you’re looking for more structured guidance on managing feeding challenges and supporting children’s nutrition, our comprehensive courses, like ‘Fussy Eating‘ and ‘Healthy Eating for Children,’ are designed to provide you with practical strategies and expert advice.

CTA Button: Explore Courses

Evidence-Based Practice

You want your advice to be backed by solid research, and there’s plenty out there. Both the British Nutrition Foundation And the NHS provide guidelines on toddler nutrition, including portion control and nutrient intake.

Common Myths About Toddler Nutrition

Let’s tackle some common misconceptions that you might encounter from parents:

- Myth 1: Toddlers Need Lots of Fruit Juice

In reality, too much juice can lead to sugar overload and cavities. Stick to water and milk as the primary beverages! The NHS recommends that children aged 1-3 should consume no more than 150ml of juice a day, ideally served as part of a meal.

- Myth 2: Fat Should Be Restricted

Healthy fats are essential for development—so don’t shy away from foods like avocados and nuts! Research supports that children require fats for brain development, and restricting them can lead to nutrient deficiencies.

- Myth 3: Carbohydrates Are Bad for Toddlers

Many parents worry that carbs will make their little ones gain weight, but toddlers need carbohydrates for energy. Complex carbohydrates from whole grains, fruits, and vegetables are vital for their growth and play.

- Myth 4: Snacks Are Unhealthy and Should Be Avoided

Some believe that snacking leads to poor eating habits, but healthy snacks can actually support toddlers’ nutritional needs. Offering nutritious snacks between meals can keep energy levels up—think fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

- Myth 5: All children Love Vegetables

It’s common for parents to assume that if a child doesn’t like vegetables, they must be picky. In reality, many children go through phases of rejecting certain foods, including vegetables. Research shows that it often takes several exposures to a new food before toddlers will accept it.

- Myth 6: Toddlers Should Finish Everything on Their Plate

While some parents believe in encouraging children to clear their plates, this can lead to unhealthy eating habits. Teaching toddlers to listen to their hunger cues is essential. Allowing toddlers to stop eating when they feel full fosters a healthy relationship with food.

Recipes for Success

To make your life easier, here are three delicious, nutrient-rich recipes to keep those little ones satisfied:

Breakfast: Banana Oat Pancakes

These fluffy, delicious pancakes are a great way to kick-start the day with energy and nutrients. They’re packed with fibre, potassium, and natural sweetness from the bananas, making them a healthy favourite for children and adults alike.

Ingredients:

- 2 ripe bananas

- 1 cup rolled oats

- 2 eggs

- 1 tsp baking powder

- 1 tsp vanilla extract

- 1/2 cup milk (any type: almond, oat, or regular)

- A pinch of cinnamon

- Optional: a handful of blueberries or chocolate chips

Instructions:

- Mash the bananas in a bowl until smooth.

- Add the eggs, vanilla, and milk to the mashed bananas and whisk together.

- In a separate bowl, combine the oats, baking powder, and cinnamon.

- Slowly mix the dry ingredients into the wet ingredients until combined. If using blueberries or chocolate chips, fold them in.

- Heat a non-stick pan over medium heat and lightly grease with oil or butter.

- Pour small amounts of batter onto the pan, creating mini pancakes. Cook for 2-3 minutes on each side until golden and fluffy.

- Serve with a drizzle of honey, or extra fruit on top.

Cultural Adaptation: For a vegan option, substitute eggs with a flaxseed mixture (1 tbsp ground flaxseed mixed with 3 tbsp water for each egg) and use plant-based milk.

Lunch: Mini Veggie Frittatas

These mini veggie frittatas are perfect for lunch. They’re protein-packed, easy to make, and ideal for sneaking in extra veggies. They can be eaten warm or cold, making them great for lunchboxes too!

Ingredients:

- 6 large eggs

- 1/2 cup grated cheese (or dairy-free cheese)

- 1/4 cup milk (or plant-based milk)

- 1 cup chopped mixed vegetables (bell peppers, spinach, courgette, cherry tomatoes)

- Salt and pepper to taste

- 1/2 tsp paprika (optional for extra flavour)

- Olive oil for greasing

Instructions:

- Preheat the oven to 350°F (175°C) and grease a muffin tin with a little olive oil.

- In a bowl, whisk the eggs, milk, salt, pepper, and paprika.

- Add the chopped vegetables and cheese to the egg mixture and stir to combine.

- Pour the mixture evenly into the muffin tin, filling each about 3/4 full.

- Bake for 15-20 minutes or until the frittatas are golden and cooked through.

- Let them cool slightly before removing from the tin. Serve with a side of salad or fruit.

Cultural Adaptation: If dairy is an issue, swap out the regular cheese and milk for dairy-free versions, and you’ll still have a tasty, satisfying lunch!

Dinner: Sweet Potato and Lentil Stew

This hearty sweet potato and lentil stew is a comforting and nutrient-dense meal perfect for dinner. It’s loaded with plant-based protein, fibre, and vitamins, making it ideal for growing children and adults alike.

Ingredients:

- 2 medium sweet potatoes, peeled and diced

- 1 cup dried lentils (red or green)

- 1 onion, chopped

- 2 garlic cloves, minced

- 1 can diced tomatoes (14.5 oz)

- 4 cups vegetable broth

- 1 tsp ground cumin

- 1 tsp paprika

- 1/2 tsp turmeric

- Salt and pepper to taste

- 2 tbsp olive oil

- Fresh coriander or parsley for garnish

Instructions:

- Heat olive oil in a large pot over medium heat. Add the chopped onion and garlic, sautéing until softened and fragrant (about 5 minutes).

- Add the cumin, paprika, and turmeric to the pot, stirring for about a minute until the spices are fragrant.

- Add the diced sweet potatoes, lentils, and diced tomatoes. Stir to combine.

- Pour in the vegetable broth, bring to a boil, then reduce the heat and let it simmer for about 25-30 minutes or until the lentils and sweet potatoes are tender.

- Season with salt and pepper, adjust spices as needed, and let it simmer for an additional 5 minutes.

- Serve hot, garnished with fresh coriander or parsley. Pair with crusty bread or rice for a more filling meal.

Cultural Adaptation: This stew is very versatile! For a protein boost, you can add chickpeas, chicken, or tofu. If you prefer different veggies, feel free to swap out sweet potatoes for butternut squash, carrots, or your preferred vegetables.

For caregivers who want to dive deeper into child nutrition, we offer several courses covering topics like ‘Fussy Eating,’ ‘Reflux, Colic and Food Sensitivities,’ and ‘Starting Solids,‘ all designed to support you in promoting healthy eating habits from the very beginning.

Building Healthy Habits

Nutrition isn’t just about fueling little bodies; it’s about nurturing a positive relationship with food that lasts a lifetime. Those who care for toddlers have the incredible opportunity to help them develop healthy habits that will serve them well into adulthood.

So, remember to keep things balanced: offer a wide variety of foods, monitor portion sizes, and create a relaxed, enjoyable mealtime environment. Trust those little ones to listen to their bodies, and guide them gently toward making healthy choices. Together, you’re laying the foundation for their lifelong health and well-being.